Concept Ideation

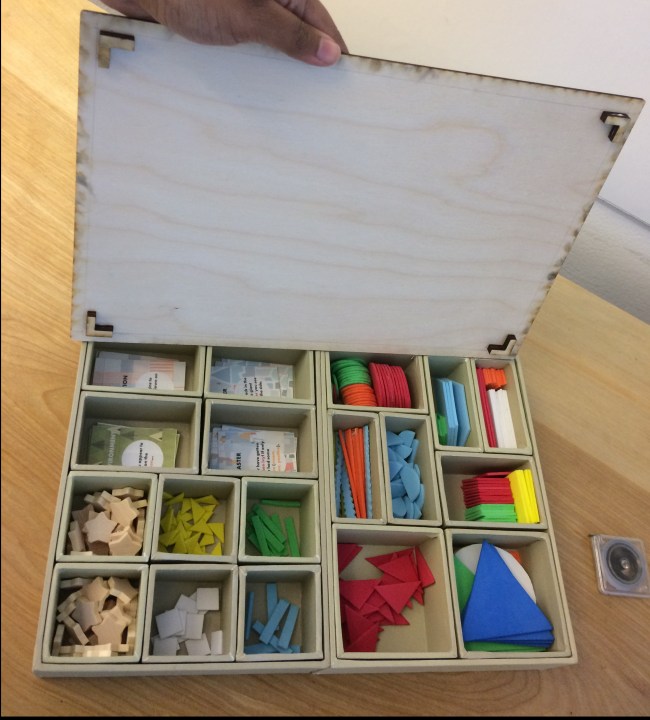

My game design team (Teesta Das, Yuchen Tong, Yang Qian, and I) started by discussing different gestalt principles, and defining affordances and signifiers, the potential topics of focus for our game. We quickly became interested in the idea of working with groups of small shapes—they could be used to make images that, because of their simplicity, would rely on gestalt principles to be visually identifiable; they could also employ signifiers to create meaning, for example turning a simple rectangle into a door by adding a round shape to it, which signifies a door knob.

Some early ideas included a more puzzle-like game, where players had to add the right shape to a larger piece to get to the next step of the game. We also considered a communal building game, where players took turns adding one shape at a time to the image, such as ‘a cat’ until it was complete or recognizable. This version of the game, however, suffered from having no clear metrics for what success of the task was. This was a problem we frequently encountered as our ideas progressed—how do you measure what is correct and what isn’t?

Because our game was a ‘discovery game,’ early on we were intrigued by the idea of a choose-your-own-adventure style game. The many avenues would keep the game interesting for repeated plays. We played with the idea of a story and plot points, until we settled on a version of our final game where each plot-point is a prompt that you have to build with shapes, and get other players to guess.

An early version of was too free-form, and involved the story being built through consensus—a player built a shape, and whatever the other teammates agreed it looked like was the next plot point in the story, regardless of what the builder intended. Next we tried to give the builder various options to build that would make the story make sense, and if it didn’t make sense players would have a hard time guessing the build from the context of the story. These versions were too weak on metrics for success or failure, and were too vague to be engaging.

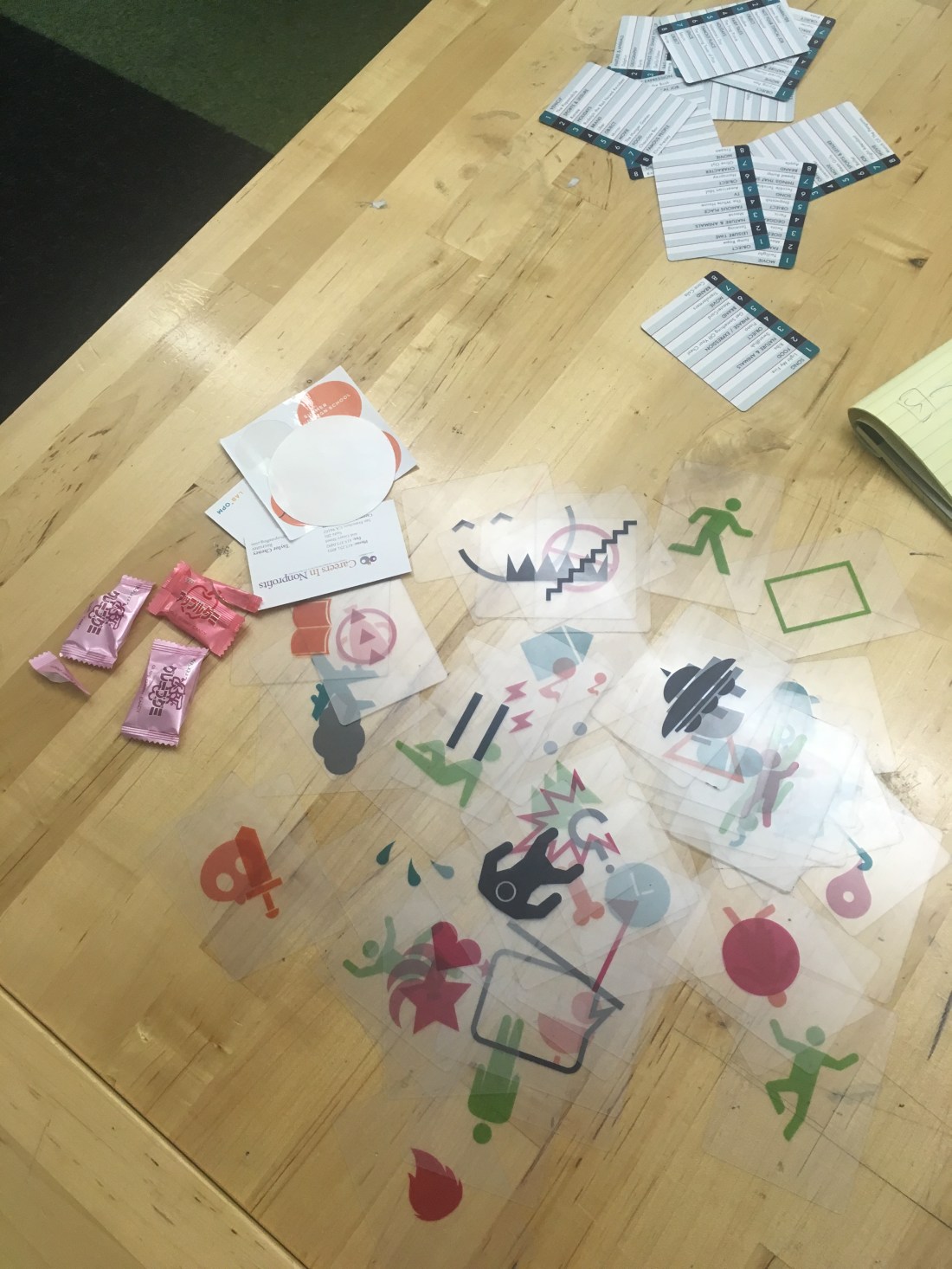

Eventually we settled on the basic premise of our final version, with a single prompt on each card that had to be guessed by other players, similar to Pictionary or Charades. Once we started play-testing, we realized how many variations of this could be played, depending on how you distribute points, the turn order, when the game ends, who wins etc. In our first play-tested version of this game, we played with trying to get the most cards (like in Apples to Apples), using cards to mark point, and a system where the winner would be the first person to get rid of all the cards in their hand. However, players quickly realized they could prevent someone from winning by refusing to guess what their last card was.

Reflection on the process

The game design process was exciting but also challenging. It could be hard to let go of vague but intriguing ideas, and we were not really able to take the time to let these ideas percolate and form into full-fledged concepts. It was a very quick process, which probably had some benefits but I felt like a lot of really unique ideas were tossed aside because we couldn’t make sense of them immediately.

Working with teammates on this process was similar in that I had to set aside ideas I wanted to explore more, because no one else seemed to be interested in going that direction. However, the process was quite rewarding nonetheless because I think we were all able to contribute ideas that pushed the process forward and that made it into the final form of the game. It was also very exciting to realize a teammate was understanding the concept or theme I was trying to express, and coming up with their own interesting suggestions on how to play with that! The process of adding to each other’s ideas and seeing something tangible grow out of it was very rewarding.

Next time, if I were to undertake another game design, I would want more personal time to sit with ideas and focus more on how it could work, rather than immediately moving on. I would also like to spend a lot more time as a team play-testing—because of our schedules, we did not get a lot of group time in the same place to test all the different variations on rules that we considered, especially before presenting the game to others to play.